The Ukrainian Success Story Continues

Meet the team behind the ten-year running programme “Schools for Democracy” in Ukraine.

by Veslemøy Maria Svartdal

“We used to be a small project that wanted something very new from the schools. Something very different. Very strange,” laughs Khrystyna Chushak, Programme Head Expert.

The EWC Ukraine team is assembled at the headquarter in Oslo to plan a new three-year period of the “Schools for Democracy” programme. Through several years of pandemic and full-scale war, meeting face to face is a rare luxury.

The programme has been running in Ukraine since 2015. Over 140 000 teachers have so far received training through the programme. 300 schools have taken part in the project, and more than 15 online courses have been developed to equip educators with more democratic and inclusive teaching skills. The work continues even under war time conditions.

PHOTO: Senior Advisor Marta Melnykevych-Chorna, Senior Advisor Nataliya Yeremeyeva, Advisor Tetiana Zaichko, Head of Early Childhood and School Section Iryna Sabor, Programme Online learning Coordinator Andriy Donets, Blended Learning Coordinator Olha Donets, Programme Head Expert Khrystyna Chushak and School Component Coordinator Olena Shynarovska.

Iryna Sabor, Head of the Early Childhood and School Section, has led the programme from the very beginning. For her it all started with the Revolution of Dignity (Euromaidan), the mass protest movement for cooperation with the European Union, and against corruption and abuse of power, which led the then-president Viktor Yanukovych to flee the country and a new government to be elected in 2014.

“I was quite active at Euromaidan in Oslo and worked with media on behalf of the Ukrainian community,” says Iryna. “I also visited Maidan in Kyiv. Right after [President Petro] Poroshenko shaped a new government, EWC Director Ana Perona-Fjeldstad and I flew to Kyiv. Together with Khrystyna we met the new reform-oriented, pro-Europe and very proactive Minister of Education, Liliya Hrynevych. We discussed the concept of a programme to support democratic reforms. This programme then received support of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”

PHOTO: Khrystyna (left) and EWC’s Executive Director Ana Perona-Fjeldstad (right) meeting with the Minister of Education and Science of Ukraine, Lilyia Hrynevych, Feb 2019

The New Ukrainian School reform

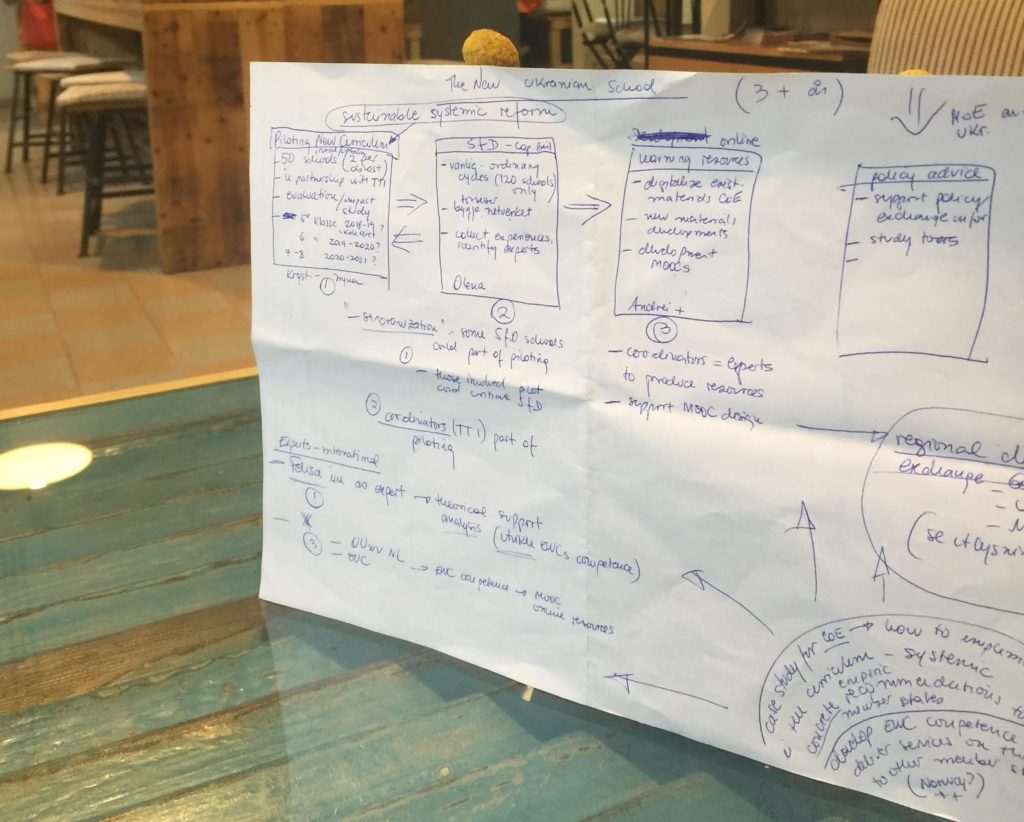

The programme started small with a few projects for youth in Kyiv and Crimea but gained steam in 2016 when the “New Ukrainian School” reform was launched. EWC was present at the development stage, giving advice and making sure that the new educational policies aligned with the Council of Europe’s Reference Framework for Competences for Democratic Culture.

The reform was aimed at reversing the Ukrainian Soviet legacy of strict hierarchy, memorization and discipline, in favour of nurturing social and civic competences in the students, enhancing their knowledge of democracy, justice, equality and human rights.

So far, the programme has contributed to develop 14 key policy documents, including “National Curricula for Pre-School, Primary and Basic Secondary Education”, “Quality Guidelines for Schools in Ukraine”, and “Concept for Development of Civic Education in Ukraine.”

“It was a very open and transparent process,” tells Iryna about the reform development. “The ministry included the civil society, parent associations and international donors. It was a period of unique unity and social partnership. Civil society was highly engaged and wanted to contribute to and control the reform implementation. We could trace our ideas and suggestions in the national curriculum, in the school quality standards, and civic education concept.”

The Minister of Education Liliya Hrynevych was open to new ideas and wanted to learn from the experiences of other European countries. The ideas of critical thinking, child-centred learning and life-long learning promoted by the EWC, suddenly didn’t seem so strange and different anymore. With the “New Ukrainian School” reform, they became state mandated.

PHOTO: In 2019, EWC received a Certificate of appreciation in recognition of its work for educational reform in Ukraine. Here former Minister of Education and Science Lilyia Hrynevych and Programme Coordinator Andriy Donets.

“We started off small with among other things a project in Crimea. But things really kicked off when I met Lilyia Hrynevych randomly at a conference in Cyprus in 2017,” remembers Ana.

“We had breakfast together at 07 AM, and for two hours straight she outlined her vision for education in Ukraine. Two weeks later, after intense follow-up discussions with our partner NGOs in the country, we handed a finished project outline to the Norwegian foreign ministry. As Director for EWC, I have met many politicians, but few impressed me as much as Hrynevych and her successor, Anna Novosad. They knew exactly how they wanted to reform the Ukrainian educational system and what future they wanted for the next generations. They stole my heart.”

“It Was a Golden Time”

One of the first tasks of the Ukraine team was to set up a dedicated pool of trainers that could be sent across Ukraine to train teachers locally in the schools. An open call for trainers resulted in a pool of 78 professionals who all went through specialized training in different locations in Ukraine.

An open call for schools wanting to participate in the programme was also held. Some were small village schools with 100 pupils, others were big city schools with more than 2,000 students.

In December 2016, EWC’s Executive Director Ana Perona-Fjeldstad received a clear request from the Minister of Education and Science, Liliya Hrynevych, to develop a manual for transversal development of democratic competences in various school subjects.

This resulted in the manual “Civic Responsibility: 80 exercises for Development of Civic Competences at 12 School Subjects,” helping teachers introduce democratic competences across history, mathematics, geography and other subjects. Already presented at the National conference in Kyiv in June 2017, it is currently recommended by the Ukrainian Ministry of Education and Science for use in all schools in the country.

“We developed a tool for Democratic School Development used for planning, monitoring progress and evaluation in 2016 and piloted it in schools for feedback,” explains Senior Advisor Marta Melnykevych-Chorna. “It was meant to empower both teachers and students, and create a democratic environment in the schools, as well as teach them how to resolve conflicts and how to partner with the parents and the local community.”

“The teachers were overworked,” remembers Marta. “They didn’t want even more tasks to do, so we had to make it easier for them.”

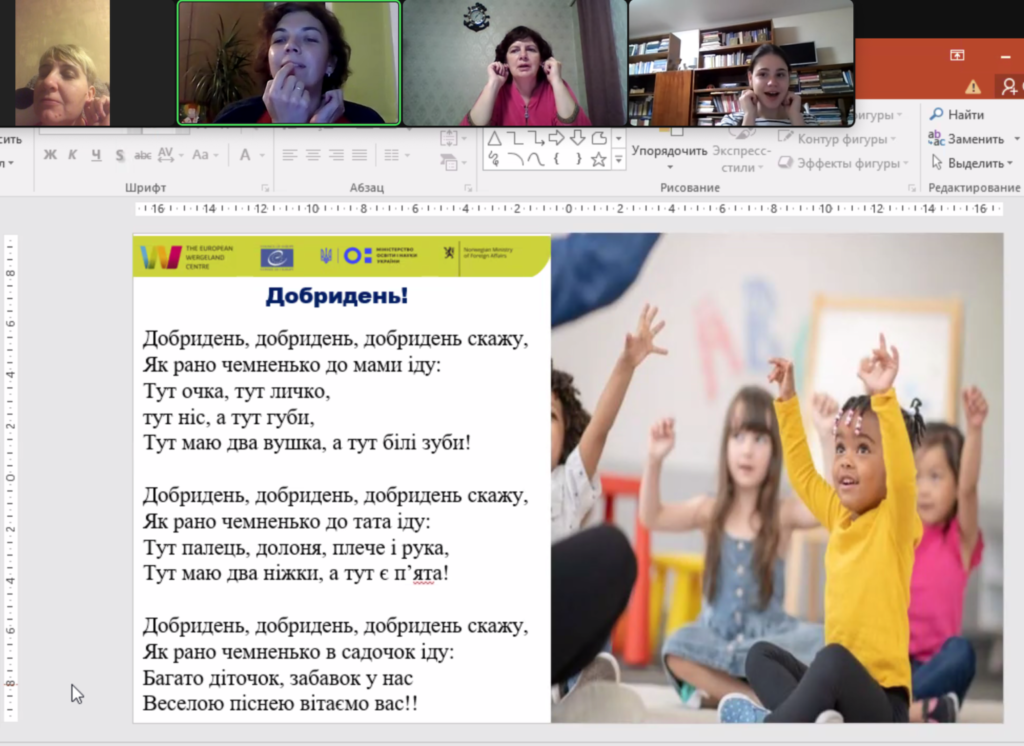

Following the manual, a number of handbooks and courses have been made for Ukrainian educators in formal and non-formal education. The latest group to be included in the project are kindergarten teachers, who became part of the programme in 2021, after a reform of early childhood education and care was launched the year before.

READ ALSO: Let Us Talk About Kindergarten

“It was a golden time when Ukrainian society was united in its determination to democratize the country, and the government had a clear and powerful vision of the reforms,” remembers Iryna. “The timeline for democratic reforms in education was constructed for 15 years, and they are continuously implemented more or less consequently even now.”

Moving the Project Online

During the Covid pandemic, as schools in Ukraine and the rest of the world closed their doors, much of the project’s activities were moved online. The trainers had to obtain new skills and methods. Luckily, the “Schools for Democracy” project had already ventured into online learning in 2019 with two courses for teachers and headmasters.

In 2020, the EWC created a series of massive open online courses (MOOCs) which were launched on Prometheus – Ukraine’s leading online course platform. The courses encompassed topics like school governance, active student participation, and development of civic competences.

The ability of the trainers to transfer their online skills to local teachers, made it possible to maintain the cooperation with schools even through the pandemic. Over 250 meetings were held online and 148 face-to-face.

On February 24th 2022, the conflict simmering in the eastern part of Ukraine escalated to a full scale war when Russia invaded Ukraine from the east, south and north.

Suddenly, EWC didn’t only have to support Ukraine through a comprehensive education reform, but through a full-scale war that so far has seen one in seven schools either damaged or destroyed, and two thirds of Ukrainian children displaced from their homes.

“When the full-scale war started, we were paralyzed for a month. Then we started to come up with ideas for wartime. We shut down the entire website and removed the school network, fearing it would be dangerous,” remembers Marta.

Violence against the civilian population, displacement and occupation, as well as frequent attacks on civilian infrastructure, has put Ukraine’s education sector under significant strain.

“Already in April we had the idea of mobile youth groups to help internally displaced persons. We used our own network of trainers, many of whom have a background from youth work, to establish mobile teams who could try to help the refuge children and talk with them,” remembers Olha.

Right from the get-go, teachers became a vital part of the war effort, sheltering displaced people, coordinating volunteer work, and conducting lessons for students both in Ukraine and abroad.

Many trainers were internally displaced themselves, but continued to work with the programme, facilitating online courses and in-person meetings where possible. For EWC it became important to figure out how to support the teachers, while at the same time forwarding the education reform.

“Our trainers told us in 2022, that those schools who performed well within our programme were better off during the war, especially in the first few months. There was good cooperation with the parents and the community, and when they were sheltering refugees they could cope better,” says Olena.

“Melitopol fell very early and almost everyone left. They are all over the world, but they have still kept their school network and continue to learn together,” adds Khrystyna.

READ ALSO: A recess from the War

The extensive online course platform developed during the pandemic proved to be a massive asset during wartime conditions. All online courses were adjusted to the war situation, updated with components on psychological support and stress management, and made available on the EWC online learning platform. So far over 78,000 people enrolled in courses after the full-scale invasion – many tuning in even while living through air raids and power outages.

READ ALSO: A Tribute to the Courage and Endurance of our Ukrainian trainers

“We have been in Ukraine during ten very challenging years – revolution, war, pandemic. You have to be flexible and adjust in order to stay relevant, and all this in a high tempo,” smiles Iryna.

PHOTO: The EWC team together with Ambassador of Norway to Ukraine, Ole Horpestad, at Closing National conference organized in Kyiv, 2019

Focusing on Ukraine’s Youth

To ensure lasting impact, the EWC has formed partnerships with a variety of public and civil society organizations in Ukraine. Wanting to focus more efforts on youth living in Ukraine, EWC signed a partnership contract with SavED foundation running the UActive programme, an organization which empowers teenagers from de-occupied regions to take on an active role in rebuilding their communities. As a partner, EWC supported youth from ten schools in de-occupied areas in northern Ukraine to develop their own school-community projects.

In 2024, in cooperation with SavED, EWC held an event at the Nobel Peace Center on the state of education and youth participation in Ukraine since the full-scale war.

PHOTO: SavED and EWC partners together with the subjects of the documentary film “WE ARE U” Danil Arabadzhy (18), Darina Zvoryhina (18) and Darii Kuzminskyj (16) at a film screening in Oslo.

Despite massive displacement, 4.5 million children still live in Ukraine. Prolonged separation from classmates and teachers is causing many Ukrainian children to lose essential communication and social skills. Whereas 64 % of students in Western part of Ukraine can still study in-person, in the frontline regions the number is only 14 %. The stress of frequent air raids, power outages and worrying about members serving in the army is taken its toll on the Ukrainian youth.

During the event a screening was held of the documentary “WE ARE U,” which follows five young Ukrainians trying to improve the future of their country.

“I want to show that Ukrainians aren’t just victims of war, but fighters too,” said Darii Kuzminskyi, one of the subjects of the film while attending the event in Oslo.

The “Schools for Democracy” Programme Continues

In February to June 2024, Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research (NIBR) at Oslo Metropolitan University carried out a mid-term evaluation of the Schools for Democracy Programme, underlining the success of the programme, and recommending an enlargement of the project.

READ ALSO: Recommends expansion of “Schools for Democracy”

In November 2024, the Ukraine team received a grant from The Nansen Support Programme for Ukraine, which ensures the further operation of the project for a three-year period.

“When we got the support, I felt a lot of responsibility to use the support in the best way, to stay highly relevant, efficient, and provide high-quality support for Ukrainian education,” explains Iryna.

A major challenge for Ukraine as the EWC team sees it, is enhancing the democratic resilience of its society and its ability to respond democratically to the challenges posed by the war and the subsequent recovery.

According to Iryna, the recent focus on youth in Ukraine will continue for the next three-year period:

“In the future we will work more to support youth participation and their active engagement in the recovery of local communities. We will help teachers develop competences to help students be more resilient to undemocratic developments and influences. We will also modify and restart our work to support the development of democratic practices at schools. This will contribute to stronger and more resilient educational institutions.”

Recalling the tender start of the “Schools for Democracy” project in Kyiv and Crimea, Iryna smiles: “It’s all coming full circle. After ten years we will again work with youth!”

The “Schools for Democracy” Programme is implemented by the EWC in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, Center of Education Initiatives, Step by Step Foundation Ukraine and SavED. The programme is funded by the Nansen Support Programme for Ukraine. The Nansen Programme belongs to the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).

Visit the programme website at https://www.schools-for-democracy.org/ or https://theewc.org/countries/ukraine/