“A Free and Open Society is Not as Easy as a Dictatorship”

Russian activists opposing the Russo-Ukraine War came to Norway to share ideas on how they could spread democratic competences to Russian-speaking communities in Europe.

by Veslemøy Maria Svartdal

Marking the end of the project “Practicing Citizenship,” – which since 2012 has aimed to promote a democratic culture in Russia – 50 Russian civic actors met in Norway to discuss the role of diaspora in a time of aggressive militarism and contempt for human rights.

Exiled, but not silenced, the group gathered one final time to share ideas on how they could spread democratic competences to Russian-speaking communities in Europe.

“You need courage and understanding to realize that freedom is not a choice. It is something we were born for, and it is the only way we can feel for ourselves that we are human.”

Lena Nemirovskaya, co-founder of the School of Civic Education, speaks to a full auditorium at Utøya.

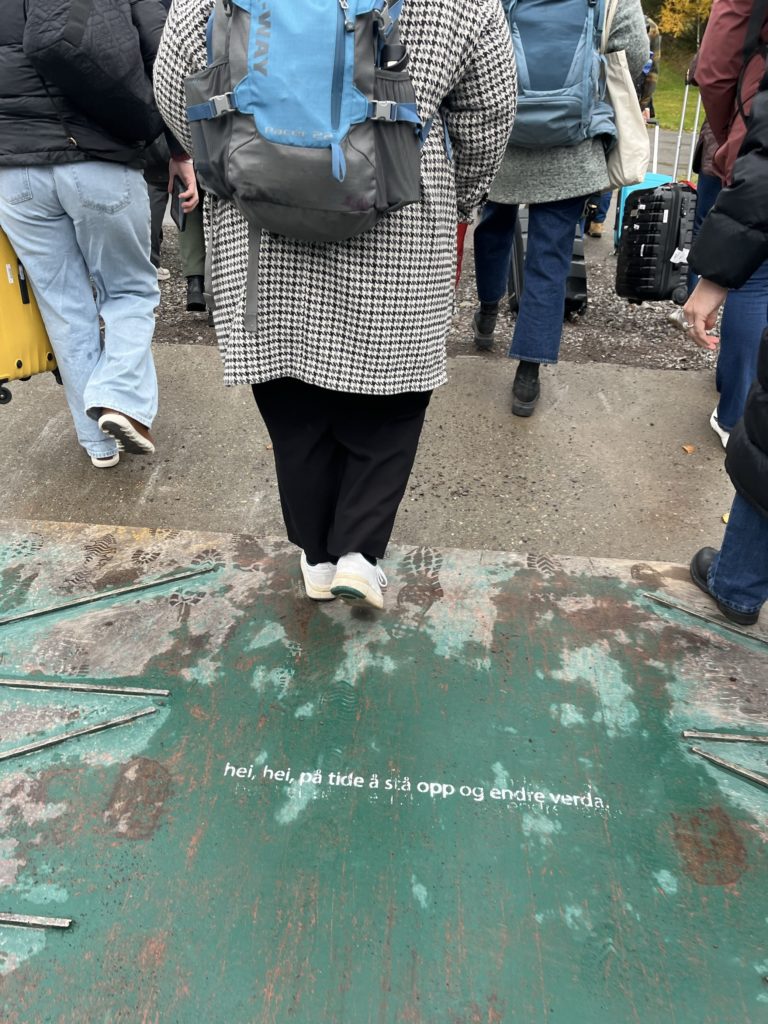

The gravity of the conference place hangs heavy in the air. This was the island where democracy was attacked in 2011. Now it hosts about 50 Russian dissidents – teachers, university professors, journalists and civil activists – who all had to flee their homeland due to their opinions and line of work.

The project “Practicing Citizenship” is coming to an end with a final conference at Utøya and Litteraturhuset in Oslo. The project aimed to help educators and other stakeholders from the Russian Federation apply the approaches of the Council of Europe (CoE) in citizenship and human rights education.

It equipped learners with competences needed to live together as democratic citizens in diverse societies, reaching thousands of educators and students from all of the Russian Federation.

“It has been a long journey,” says EWC Director Ana Perona-Fjeldstad, one of the initiators of the project. “Europe was different, and Russia was different. We hoped that we could strengthen democracy in Russia through democratic learning. Through ten years we have born witness to the transformation of the state system. In 2021, we still hoped we could bring CoE and EWC standards to Russia.”

The project was initiated one snowy March day, when Lena came to Oslo to look for cooperation partners. A conversation between Lena and Ana at the EWC office led to the launch of the project.

PHOTO: Lena Nemirovskaya sharing a moment with Ana Perona-Fjeldstad

“A Free and Open Society is Not as Easy as a Dictatorship”

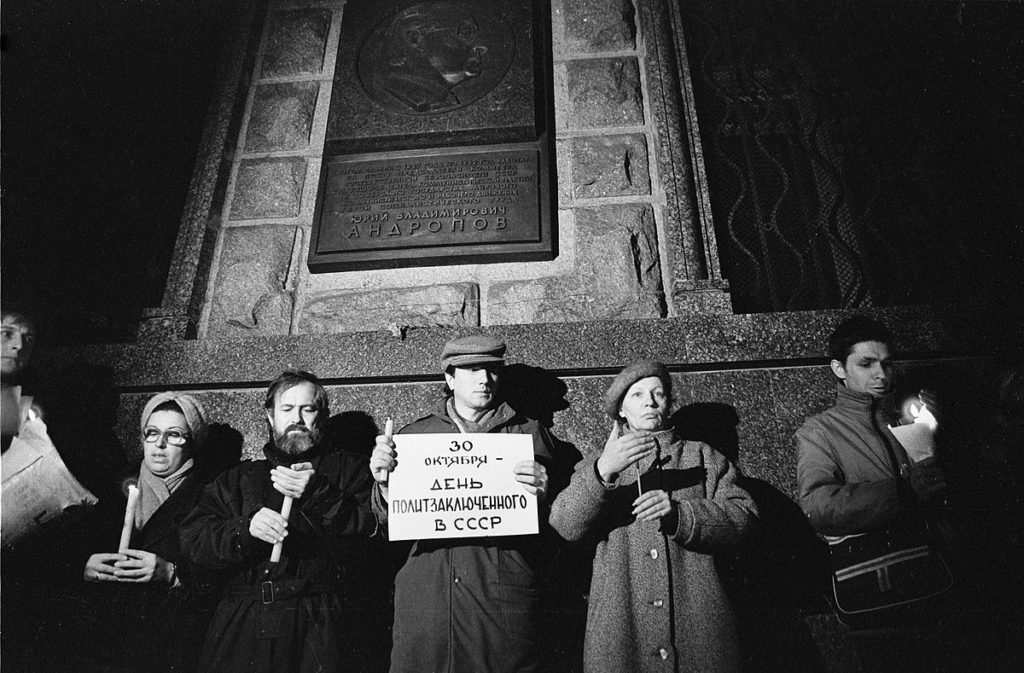

Lena grew up in the Soviet Union and was already in her 50’s when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev rolled out the liberalization reforms “perestroika” and “glasnost” to halt the decay and economic struggles of the failing Communist state. This meant an unprecedented level of freedom of both thought and speech for many millions of Soviet citizens.

“It was unforgettable,” remembers Lena. “Among us we had people from the [GULAG] camps. It was a feeling of freedom, and we shared it with people we didn’t know.”

In 1993, Lena and her husband of 52 years, Yuriy Senokosov, decided to establish a school that would help their country build a thriving democracy and strong institutions. Such knowledge was severely lacking in Russia:

“I thought we would live in a new space, but the whole experience of perestroika showed us that a free and open society is not as easy as dictatorship,” says Lena. “Even the most enlightened and most educated Soviet and post-Soviet people lacked this knowledge.”

For EWC Senior Advisor Valentina Papeikiene – who has managed the project since 2016 – it was the combination of these two approaches that spelled the success and longevity of the “Practicing Citizenship” programme:

“The combination of the two approached gave people a broader vision of the topics, and a more philosophical and academic perspective combined with very active learning methods. I think that was a very good combination that worked extremely well.”

PHOTO: Anastasia Gontareva, EWC Senior Advisor Valentina Papeikiene, Yuriy Senokosov and Lena Nemirovskaya and EWC Senior Advisor Larisa Leganger Bronder.

“I Take it as a Badge of Honour”

“Even though the Russian Federation was a part of the Council of Europe at the time, it always felt like there were challenges to working with issues connected with democratic citizenship,” says Valentina when asked about the working conditions in Russia throughout the years.

Anastasia Gontareva (right), who joined the School of Civic Education in 2008, remembers how the school only ever received one sign of recognition from the Russian government: A letter of gratitude from President Vladimir Putin. As irony would have it, it was exactly such honours and rewards the Russian government would use as proof when labelling the school as a “foreign agent” in 2013.

“I take Putin calling us foreign agents as a badge of honour,” Lena says defiantly.

In 2016, Lena, Yuri and Anastasia left Russia for the Baltics. Since then, the school has to a larger extent focused on working with participants based outside of the Russian Federation.

Relaunching the Project

In spite of the ever more difficult working conditions, the “Practicing Citizenship” project carried on operating right until Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

“Before 2022, we worked with teachers, university representatives, teacher trainers and civil society organisations. We had planned the same things for 2022 and onwards, until the full-scale invasion happened,” remembers Valentina.

It was soon deemed impossible to continue working inside Russia. The project was put on hold until autumn 2022, when it was relaunched focusing on Russian civic educators in exile in Europe.

Due to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, tens of thousands of Russians educators, civil activists and artists had by then left the country, and EWC decided it was important to strengthen the democratic forces in the Russian diaspora – believing they could play a crucial role in promoting human rights and democracy.

“We started to work with the diaspora, which was a new group for the EWC, and decided that we would focus on three main target groups: Civil society representatives, educators working in exile, and youth. We held a series of local and international seminars in several countries, including Norway, Montenegro, Armenia, Lithuania, and Hungary.” explains Valentina.

During the past two years, the project has reached 200 civic activists in exile.

Through the reimagined project, Russian educators and other civic actorswas given training in how to spread awareness about education for democratic citizenship and protection of human rights throughout Russian-speaking communities in Europe, providing them with an alternative to the militaristic and authoritarian education model of the Russian federation.

“Thematically we focused on topics such as how to teach and work with controversial issues, how to alight the internal process of organisations to principles of democracy and human rights, and how to build safe spaces and democratic learning environments that can be important hubs for local communities,” says Valentina. Conflict resolution and non-violent communication were also important for us, considering what competences are needed by participants of a democratic community.

“We can’t lose touch with the people within Russia”

EWC courses challenge participants to apply the new competences developed in their own activities, this is an important aspect of the EWC methodology allowing to try out and incorporate new tools and practices into everyday practice). The relaunched Practicing Citizenship project was no different. At the concluding conference, participants detailed how they had applied the knowledge gained from the project in their own initiatives in their new homes.

Vladimir Shmelev shared how he used the EWC-taught whole-school approach as a basis for all his civic education initiatives belonging to the “Adriatic” school network in the cities of Bar, Herzeg Novi and Podgorica in Montenegro.

Lydia, working at a Russian-language school in Georgia, participated at EWC trainings in Armenia. There she learned how to organize school after the whole-school principals, and how to incorporate activities from the COMPASS manual in their lessons.

PHOTO: During the conference,. time was also given to researchers to present their findings. Here senior researcher Helge Blakkisrud at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs presents the latests developments in education in the Russian Federation.

Aidar, a former journalist, participated in a responsible leadership training course in Budapest. When his radio station was closed by the Russian authorities, he and a colleague decided to found a podcast in exile in order to bridge the gap they felt were growing between them and their countrymen still remaining in Russia.

“We can’t lose touch with the people within Russia,” Aidar explains, “I was at an anti-war rally in Berlin this fall, and everyone were shouting different slogans. Some were saying: ‘Russia is us.’ But Russia isn’t only us, and we have to find a language to communicate with the people we disagree with inside Russia. Because the Russia of tomorrow will still contain these people.”

Denis Grekov, former senior lecturer of Critical Thinking at the Russian Presidential Academy in Moscow, was forced into exile due to a Facebook post condemning the invasion of Ukraine. He now lives in Krakow and continues to teach critical thinking to students online. Grekov participated at the Education in Putin’s Russia Conference in 2022, which resulted in the report “Education in the Service of Ideology and Political Gain – The case of Russia” which was finalised in December 2023.

“We Created a Space Where People Really Felt Their Dignity is Respected”

Asked about her best memories from the project, Valentina wants to highlight two:

“Before February 2022, we were organizing a conference, and after the event, one of the school directors came up to me and said: “Thank you for giving us this space and for listening to us. Nobody listens to us.” After 2022, again the words of the educators that said: “We feel a lot of efforts are made to support activists and journalists. We understand why it is so, but thank you for not forgetting educators. Sometimes we feel like we are left alone.” We created a space where people really felt their dignity is respected, and that they are important actors in the education system, who can actually make a change.”

“In Russia there will always be progressive and regressive trends. There will be people who will bring enlightenment to freethinkers. It may not be the leading trend, but we are working to create more people like that, because if there are more people like that, they will be able to have more impact,” says Anastasia.

The Practicing Citizenship project was financed by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.