“Suddenly They Want to Go to School”

How a Democracy Project Transformed Classrooms in Romania

By Veslemøy Maria Svartdal

Cristian Chiriac climbs the stage at the assembly hall in Suceava’s Sports Lyceum. He is project coordination and monitoring officer with the Romanian Social Development Fund – one of the European Wergeland Centre’s long-standing partners.

“Most of us were born in the communist period and we were moulded in that environment. That is why it is very important to integrate inclusion, diversity and democratic competences in our schools,” he explains to the gathered audience, all participants in the bilateral pilot project “Promoting Inclusion and Quality Education in Romania.“

On this sunny March day, the 8-month-long project comes to an end with a big final conference. Teachers, school heads, scientists and civil society representatives are given the opportunity to share what they have learnt during the project, and how inclusion and education in democratic citizenship can continue in the future.

The mood is eager and exited as the results are presented. Strong professional relationships have been developed during the course of the project, and many are happy to see each other again.

For when the European Wergeland Centre and the Romanian Social Development Fund launched their project in early autumn 2024, they asked one simple question:

What happens when you bring together a diverse group of professionals from two depressed Romanian regions to find ways to make their schools inclusive and based on a democratic foundation?

Read also: Mayors and Principals Come Together to Improve Their Schools

“I Promised Myself that no Child Should Face What I Faced”

Călărași, about a two-hour drive from Bucharest, struggles with rural underdevelopment, lack of opportunity and migration, either to the capital or other European cities.

“Education is very important for a small, rural place like ours,” say Liviu Moise, headmaster at the Unirea secondary school in Călărași. “There are not as many opportunities for young people as other places in Romania, so they need to stay in school in order to have a chance to compete with students from bigger cities.”

Suceava, in northeastern Romania, is burdened by widespread poverty, transport limitations and environmental challenges due to flooding and illegal logging. Like Călărași, migration is a substantial problem.

The participants hail from a range of professions: School heads, teachers, mayors, university professors, and local government representatives – a testament to this project’s unique approach.

And as is often the case, those belonging to a historically marginalised minority feel these struggles even more acutely.

When Narcis Constantin was a schoolboy, he was the only child of Roma heritage in his entire school. After experiencing high levels of discrimination and abuse, he decided to to go into teaching and now works as a teacher of Romani language, Roma culture and history at the Gymnasium Gulia in Suceava.

“I promised myself that no child should face what I faced. I will never allow discrimination to happen no matter the child’s skin colour of any other attributes,” he says.

“They Brought Back the Knowledge to Us”

Learning of the project from his headmaster, Konstantin and his colleagues received multi-day training in Suceava.

“My biggest takeaway from the project is the love you and everyone participating have for inclusion. It means a lot that you approach the Roma with such thoughtfulness, because for so many years we have been segregated,” he says passionately.

“Also, the thoughtfulness among the school heads and mayors means a lot. They went out into the outside world to learn about the problems of inclusion, and they brought back the knowledge to us. Then they sent us teachers out to learn more.”

According to numbers from the Council of Europe, approximately 1.85 million Roma reside in Romania, accounting for about 8.3% of the population, and making them the country’s largest minority. Therefore, the project afforded special attention to the Roma communities in Călărași and Suceava, following EWC’s long-running efforts to support Roma inclusion in Europe.

The Roma minority face difficult living conditions in Romania. Many live in overcrowded or informal housing without basic services like water and electricity. Discrimination is widespread, affecting their chances of finding jobs, completing school, and receiving fair treatment in public institutions.

Konstantin wants to be a role model for his students, showing them the importance of education for succeeding in life. He hopes that his students will become lawyers, teachers, policemen and doctors, and that one-day Roma patients will be able to go to the hospital and have their doctor speak Romani back to them.

Read also: “Romani Language is the Main Identity Element in our Heritage”

“The Project Was Different in this Way”

Aiming to turn negative trends and help build inclusive and quality education for students in Călărași and Suceava, all participants learnt ways to solve problems and interact with others in a democratic and non-discriminatory manner – either during study trips to Oslo or multi-day trainings locally in their home-regions.

EWC’s experienced trainer team facilitated the training, sharing key Council of Europe and EWC concepts, like the whole school approach where schools are encouraged to open their gates and bring together not just the teachers and pupils, but also the other staff members, parents and other members of the local community to build safe, inclusive and democratic school environments.

READ ALSO: “A School is not a Castle with Closed Walls”

Two trainers are themselves of Roma heritage and could with conviction and credibility share knowledge about Roma history, culture and traditions.

FOTO: Trainers Marius Jitea and Mihaela Zatreanu (middle) at a multi-day training in Suceava.

“After participating in Oslo I came back with bigger motivation to promote inclusive education,” says headmistress Mioara Lavric at the Cirprian Porumbescu school in Suceava. “What we learned in the field we could take back home to our school. More than 50 % of our pupils belong to the Roma minority. That is why I think the project is so important. When we learn about their culture and history, it helps those of us who are not Roma to understand our pupils better,” she says.

“Putting us together has been very important, and the project was different in this way. The trainers brought their personal experiences, and us colleagues did as well,” says Nicoleta Popa, school inspector in Călărași, and one of the professionals chosen to undergo a special training in Oslo to become a trainer in democracy education in her own right.

FOTO: School inspector Nicoleta Popa, trainer Ramiza Sakip and EWC senior advisor Larisa Leganger-Bronder

All in all, 37 schools, 188 teachers, 20 school heads and 20 local government representatives from seven municipalities in Călărași and thirteen in Suceava took part in the project.

“Suddenly They Want to go to School”

Returning from their seminars and study trips, all participants had been tasked with sharing their newfound knowledge with their colleagues, as well as put in motion concrete measures to promote inclusion and democratic competences in their schools.

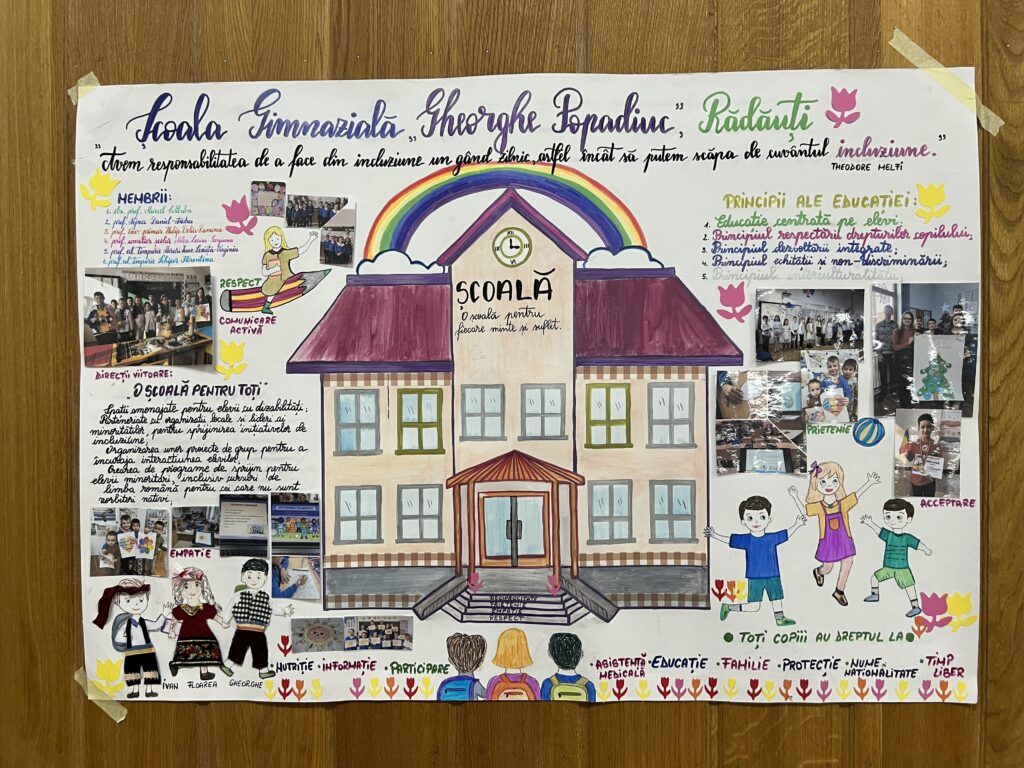

The results surround the audience in the assembly hall, either in the form of colourful handmade posters on the walls, through testimonies from school heads and educators, or from the statistics gathered by EWC senior advisor, Larisa Leganger-Bronder.

Liviu who participated in a study trip in Oslo, and recommended four of his colleagues for multi-day local trainings in Călărași, says he highly enjoyed all the activities taught by the trainers:

“I’ve used them in my classroom and the children respond well to them. We have made wallpapers about inclusion and even reels for social media,” he explains.

Konstantin teaches children from toddlers to teenagers, and he too brought what he learned back to his classroom:

“I have used exercises from the training in my classes, and the children appreciate it. Suddenly they want to go to school. They are excited about what they are going to do the next day. Of course, I don’t tell them. I want to make sure they would turn up. I taught the exercises to both Roma and non-Roma teachers. For us the project has been absolutely transformational. Attendance has risen dramatically. Now children see that learning can be fun.”

During the project, about 65 per cent of teachers had introduced new initiatives, and more than 40 per cent improved existing policies by strengthening collaboration with city halls, developing clear anti-discrimination policies in schools, and facilitating transportation subsidies for disadvantaged students.

“You are Never too Young to Learn about Democracy”

Headmaster Liviu believes good cooperation between the schools and municipalities is vital for the success of both schools and local communities:

“I speak to the mayor every day, and he understands the importance of education.”

After discussing the importance of children learning democratic competences from an early age at training in Oslo, Unirea secondary school held an election of their own for Student Council.

Excitedly, Liviu takes up his phone and shows photos of his school’s Student Council president posing with a mayoral sash – happily lent her by the mayor himself.

“We invited our pupils to hold a Student Council election, where we debated the issues that us adults had previously discussed on the trainings. The children learned about their rights and responsibilities and were able to elect one president and two vice presidents. Our student president even held a speech at the mayor’s inauguration. It is important for adults to spread the knowledge of democracy, especially considering the recent Romanian election,” he says.

Like Liviu, headmistress Mioara Lavric enjoys a close working relationship with the local mayor. And she also made changes to the democratic initiatives at her school:

“Previously, the children complained that they don’t have a voice in school concerns and that their opinion does not matter. That is why we established meetings with the teachers and the pupils, where they could raise their concerns. Before, this was reserved for older children, but at the training I received in Oslo, I understood that there was no reason why they younger ones should be excluded. You are never too young to learn about democracy.”

Laughing, Mioara explains that the younger children know very well what the purpose of the meeting are and that they are not afraid to speak their minds.

Reporting back to the European Wergeland Centre and the Romanian Development Fund, 93 per cent of the participants stated that they now actively collaborate with schools and local authorities to promote inclusion, and more than 85 per cent confirmed a deeper understanding of inclusive education and democratic principles.

“Change is Not an Easy Thing”

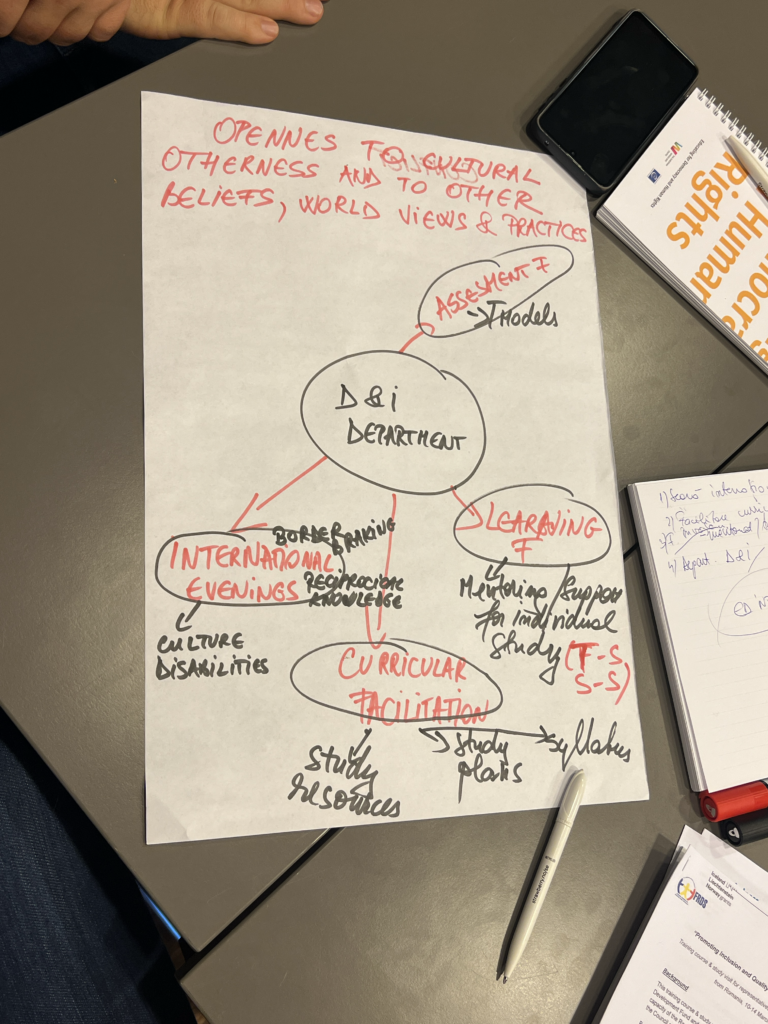

The project also included 13 university professors whose task was to develop curricular recommendations to equip future teachers with knowledge and competences in democratic citizenship, human rights and inclusive education.

“Perhaps we needed to meet in Oslo to understand that we can collaborate,” smiles Violeta-Stefania Rotarescu, associate professor in psychology at the University of Bucharest.

“You know, sometimes change is not an easy thing. Sometimes we are too tired to make changes, even when we know that it is a good thing to do. These kinds of projects push us and serves as good reminder that things can become better,” she says.

Like mayors and school heads, representatives from universities and teacher training institutions met in Oslo to partake in a multi-day seminar.

For Violeta-Stefania, the realization that fostering a democratic culture and living as a active and responsible citizen, is a lifelong commitment, was both scary and exhilarating.

“This training is not very simple. I need to transform myself to reach people. To teach democracy is a lifestyle. It’s a style of living,” she reflects.

Cristina Olteanu, who works as a Councillor for at the Ministry of Education and Research had a similar realisation:

“Democracy not only needs to be taught, but experienced,” she says. “It has been inspiring to see how we can increase the civic education awareness among the students and the professors. This entire week they have discussed how important it is to experience democratic culture directly, and how things like roleplays can achieve this. Democratic skills, attitudes and values are very important for the Ministry, and it outlines the direction we must take.”

“We Must Continue our Efforts”

Only a few weeks after the study trip, Violeta-Stefania and several other colleagues she had met in Oslo, are ready to present the results of their brainstorming with the rest of the project participants.

PHOTO: Councillor Cristina Olteanu (left) sharing her ideas with professor Violeta-Stefania Rotarescu (middle) and other project participants at a study trip in Oslo.

As they take the stage, the professors explain that the lessons which were taught during the project need to be included in the teacher training curriculum. For teachers already working in schools, even more seminars and workshops are needed.

Reflecting on their shared experience, project participants from different professions agree that teachers need support and further training to develop the proper skills needed to help guide their students. Continued dialogue between schools, students, parents and the local community is also needed to maintain and spread the positive lessons learned during the pilot project.

“Through this project we had the opportunity to connect with one another,” says Violeta-Stefania. “We felt that we would make a great impact if we helped each other. Inclusion is a lifestyle and a continues process – not a finished product. The most important thing is that we continue our efforts.”

The project was implemented under the Local Development, Poverty Reduction, and Enhanced Roma Inclusion programme and funded by the EEA Norway Financial Mechanism 2014-2021.