“Auschwitz did not Fall down from the Sky”

In a time of war and growing polarisation, museum professionals from Ukraine, Poland, and Norway are rethinking how museums can move beyond or around memory to become dynamic learning spaces for dialogue, democracy, and civic engagement.

A battered suitcase with the name of its owner painted in large, desperate letters. An enamel cooking pot. A milk jug. A plastic construction helmet decorated with flowers. An improvised cooking stove. A text message with no reply. A tombstone with Hebrew script turned into a grinding stone.

These are all small pieces of what is left after a massacre – objects that help humanise tragedies that quickly become generalised. The Holocaust. The killing of protesters on Maidan square in 2014 and the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The terrorist attack against a summer youth camp at Utøya in 2011.

What can such artefacts tell us about the past? What effect can they have on the audience and how can history museums become places of learning, reflection and dialogue in a time of growing conflict and polarisation?

Such is the task of MUCIT – Museums as Sites of Citizenship, a two-year project bringing together museum professionals from Norway, Poland, and Ukraine. At its heart is the MUCIT network: a group of 25 museum educators from several different institutions who want to empower museums as vital engines of democracy and civic engagement—especially among young people across Ukraine and Europe.

Read also: Building a Hub for Museums and Civic Education in Europe

“We work with themes that remind us of the brutal history of the past, and right now it feels as though the world again is descending into dark times,” says Iryna Sabor, head of EWC’s Early Childhood and School section and the main initiator of the MUCIT project.

“But this project is uniting us – not only in our work with traumatic events, but also our interaction with young, bright people who are eager to learn and happy to ask critical questions. We want to not only remind them of terrible events of the past but to give them hope. How can we make sure that such atrocities do not happen again?”

Exchange of Experiences

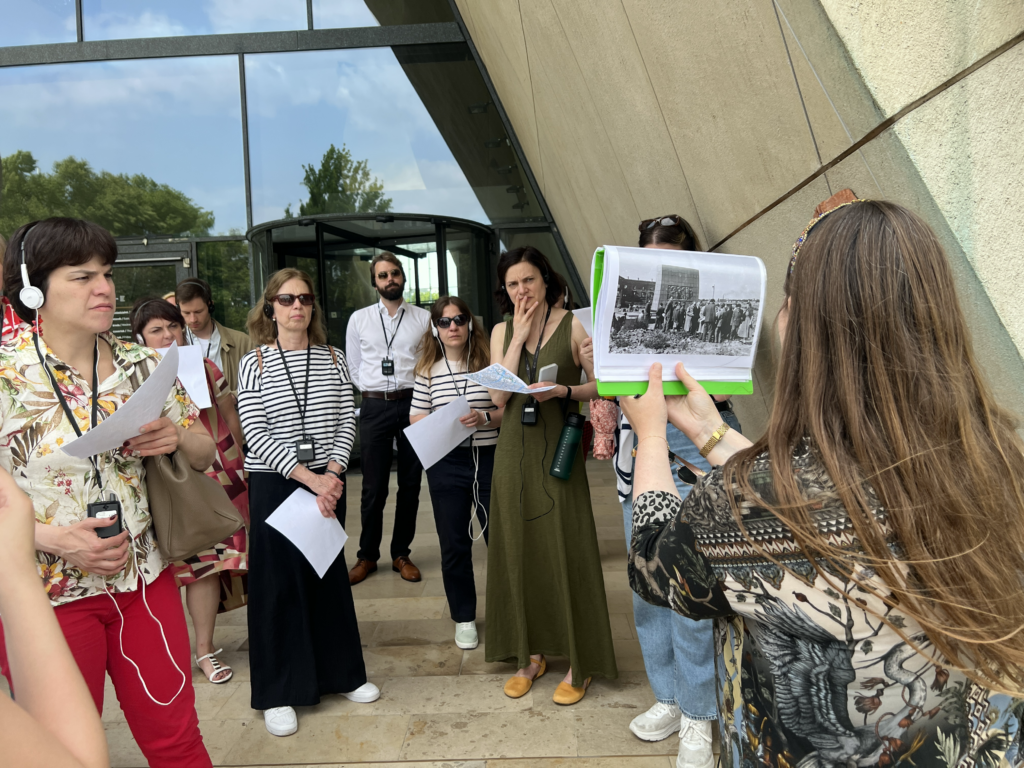

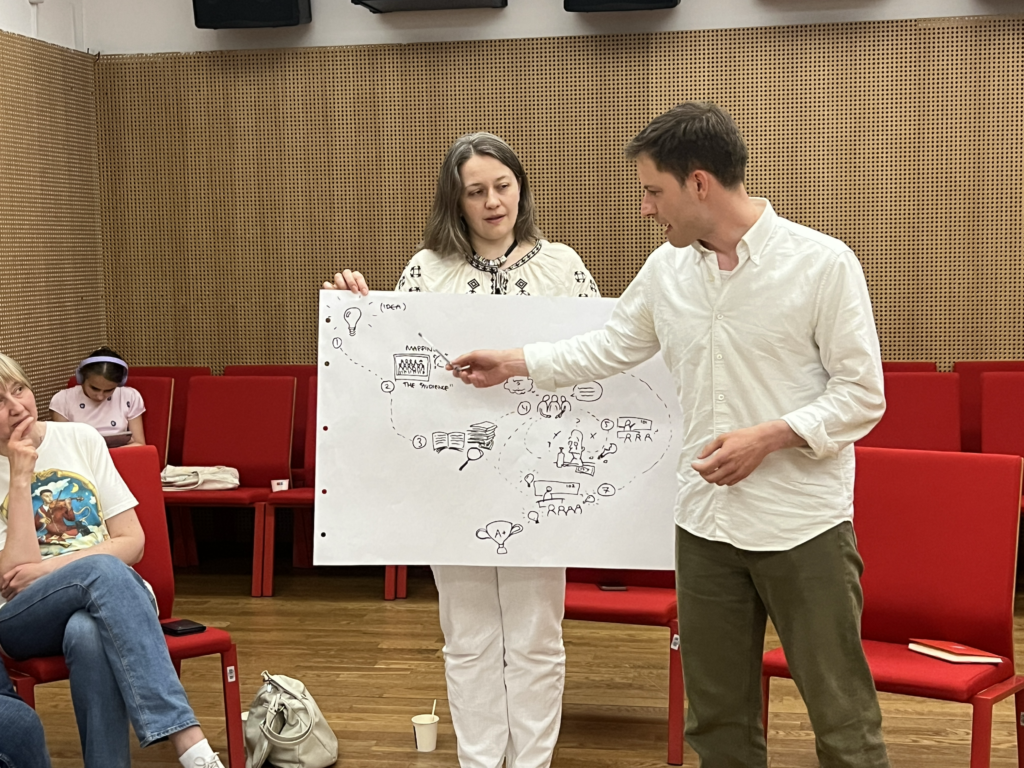

Through the project, participants engage in international workshops, helping them to learn from each other, develop digital learning materials and build a network of “museum ambassadors” among teachers and educators in Ukraine, which will strengthen the cooperation between museum educators and schoolteachers in the future.

Many of the participants met for the first time in Oslo in March 2025 to take part in the first of three MUCIT seminars and study visits. A second was held in Warsaw in June the same year, with a third to be held in the small Polish town Przemyśl, close to the Ukrainian border in September.

Visiting each other’s exhibitions and taking part in activities designed to engage younger audiences and bringing history to life, the participants also have the opportunity to discuss topics vital to their mission as museum educators:

How do you deal with trauma and controversial issues? How to work constructively with witness testimonies while at the same time telling a balanced and truthful story, open to dialogue and reflection? How do you combat disinformation and politization of memory designed to hurt others and justify war and aggression?

“I think the most important thing is the exchange of experiences and the feeling that we are working in the same field in our big world. Although we come from different countries, we face the same challenges, and we can help each other solve complex problems,” says Anastasiia Haidukevych-Kachuro, Researcher at the National Museum of the Revolution of Dignity.

Growing Controversies

Through working together in the network, participants are able to share what challenges they face daily: Holocaust trivialisation, contested memory sites, and diverging national narratives around events like WWII, the Holodomor, and the Revolution of Dignity.

Controversial topics, while often emotionally upsetting, may also serve as vehicles for democratic dialogue that call for reflection, personal growth, and action among everyone; not only youth, but practioners in the field as well.

The European Wergeland Centre has for many years supported educators and young people across Europe in navigating such issues.

“We need to acknowledge that addressing controversial issues is both important and necessary. We need to be open to constantly learning and recognise that controversial issues are an indispensable part of our lives. They can be the foundation for something good in the end, if you handle them properly,” says EWC trainer Khrystyna Chushak, who is a specialist in Teaching Controversial Issues (TCI).

Read also: Teaching controversial issues

“We first introduced the discussion of controversial issues (based on the Council of Europe manual) to the trainers of the Ukrainian Schools for Democracy Programme around 2017–2018. Our trainers agreed that this topic was highly relevant for Ukrainian schools. However, over time, we began receiving feedback indicating that, in practice, teachers often prefer to “play it safe” and avoid engaging with controversial issues in the classroom,” continues Khrystyna.

She says it is far from just a Ukrainian phenomenon. Research across Europe shows similar trends. Teachers frequently cite the same reasons for their reluctance: a lack of training in how to teach controversial issues, insufficient knowledge of the topics themselves, and sometimes fear of backlash from parents or school leadership.

Monika Koszynska, Chief Specialist of Teacher Programmes at the POLIN museum, believes that the controversies are growing in today’s societies.

“At the POLIN Museum we say that to know how Polish Jews perished during the Holocaust, one must first know who they were and how they lived here, on Polish soil. Our philosophy is as follows: No young person will grow up to be an informed, responsible and active citizen if he or she does not face the difficulties associated with the truth about the history of his or her family, locality or country,” she says.

The European Wergeland Centre has a long-standing cooperation with POLIN: Museum of the History of Polish Jews through the “Fighting antisemitism, xenophobia and racism now!” programme. Funded by EEA and Norway grants, it brought teachers and students from upper secondary schools in Poland and Norway together to strengthen their resolve to fight xenophobia and to promote attitudes of respect and inclusion.

Monika believes that museums are natural arenas for education. Using educational materials actively with audiences help the POLIN museum not only to teach about the history of Polish Jews, but at the same time derive lessons from history, try to shape a better future and avoid the mistakes of the past.

“We have told ourselves and our audiences that we will not try to hide the difficulties; on the contrary, we will do our best to discuss them in an atmosphere of respect, openness, and a desire to understand complex issues,” says Monika.

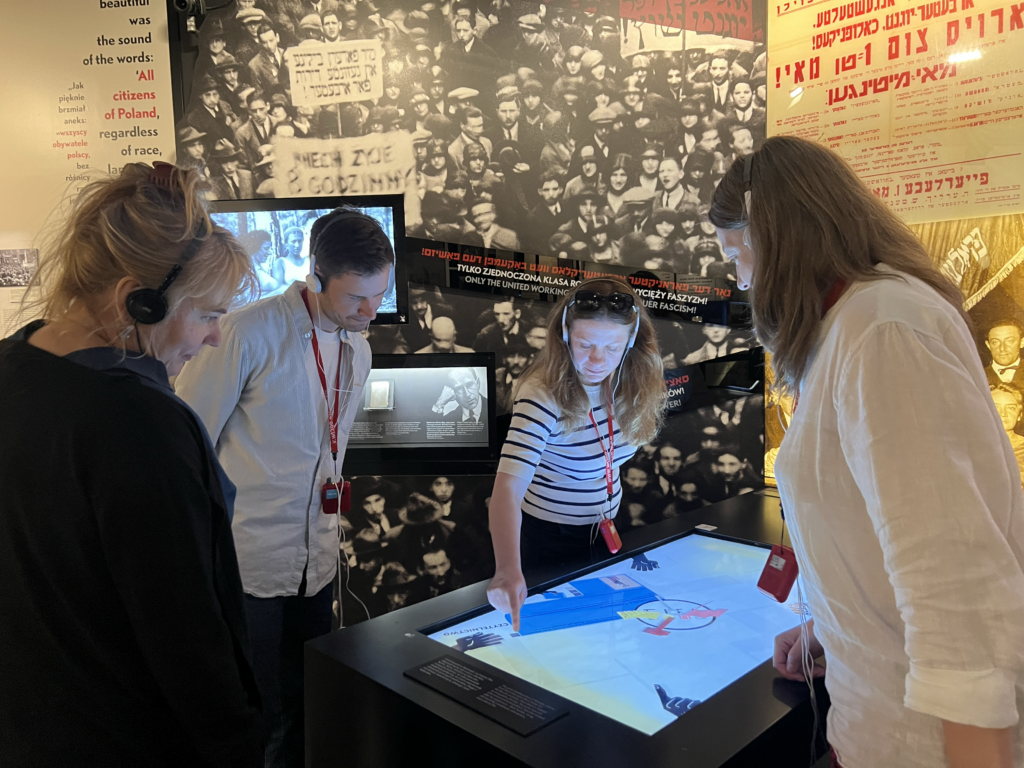

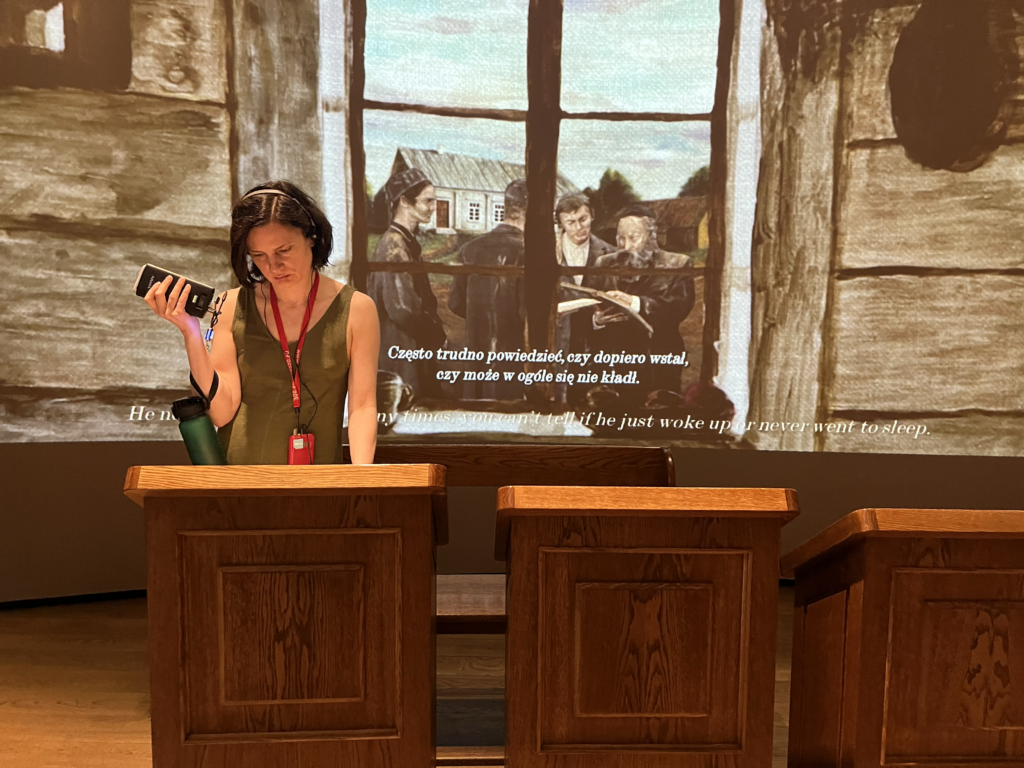

The POLIN museum tells the 1000 year-long history of Polish Jews. Built on the ground of the Warsaw Ghetto Rebellion, the museum is significant in that it has far fewer physical artifacts that other historical museums. Through persecution and genocide, much of physical world of Polish Jews has been burned, looted or torn down. The museum instead focuses in large part on telling the story through first-hand accounts and reconstructions of what a Jewish life in Poland used to look like.

What Lies Beyond the Picture

Museums preserving the memory of traumatic events have a responsibility to share knowledge about the historic atrocities and work for it never to happen again.

“Auschwitz did not fall down from the sky,” says Nataliia Tkachenko, Education Specialist at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Working at one of the largest sites of mass extermination and dehumanisation in the world, she realizes her mission by consciously mixing historical realities with the personal experiences of Holocaust survivors.

“We only have the voices of the people who survived. The voices of the people who perished are lost. We need to be aware that one account or even one image does not tell the full story. What lies beyond the picture? What does it not tell?”

Nataliia wants museums to present history in its complexity, talking about different sides and narratives, and allowing the visitor to come to informed opinions.

“Fair historical research behind storytelling is crucial. It is important to take care not to manipulate or overuse the emotional side, which is especially challenging with traumatic events from the latest history.”

During the seminar in Poland, the participants gained valuable insights from the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews and the Jewish Historical Institute.

Museums as Sites of Learning and Citizenship

Over the multi-day seminars, the MUCIT participants are able to exchange ideas and practices, built bridges between their institutions and lay the groundwork for a strong and dynamic European museum network, which they hope will continue to grow in the future – also after the project’s two-year period is over.

Another key aspect of the project is to transform the lessons learned during the workshops into educational material for teachers and educators across Europe. These lessons will be freely available online for teachers to use and will be piloted by schoolteachers in 2026.

The MUCIT participants believe that museums is an underused resource when it comes to teaching children, young people and adults the history of past atrocities, while at the same time helping them to develop democratic competences, critical thinking skills and supporting teachers in bringing younger generations up in a democratic culture of dialogue and a constructive and conscious relationships to traumatic events.

“Trying to tell the students that democracy is very important, instead of having them experience it is a very bad idea,” smiles Bendik Egge, Head of education at the Nobel Peace Center.

“It is important to have dialogue with the students as well as the teachers and provide interactive examples that have a connection to the curriculum they are working with,” he says. “We do this through a love for the teaching profession. What we want to do is support teachers.”

“Remembrance may be part of your identity but being aware of your identity and the world around you – that is what makes you a citizen,” says Nataliia.

“MUCIT: Museums as Sites of Citizenship” is a cooperation between the European Wergeland Centre, the National Museum of the Revolution of Dignity – Maidan Museum, POLIN: Museum of Polish Jews, and Utøya.

Stay Connected

Interested in learning more about the “MUCIT: Museums as Sites of Citizenship” project? Sign up for the EWC newsletter or follow us on Facebook for the latest updates!

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.